Source: Oklahoma Farm Report

The closure announced by USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins on May 11th highlights the reality that the New World Screwworm flies have broken through the natural barrier in southern Mexico, where they could have been contained. According to National Cattlemen’s Beef Association CEO Colin Woodall, it is no longer a question of whether or not we see a return of New World Screwworms in the United States; it is a matter of when that is going to happen. Woodall stated “It’ll probably be sometime later this summer.”

The flies currently exist roughly 700 miles south of Texas, and as the geographic land mass widens the further North they go, controlling them becomes more and more difficult, and more and more sterile flies are needed.

Woodall, along with his team at NCBA, acknowledges that the border closure will create economic harm for U.S. farmers and ranchers and create supply chain disruptions, but the costs will be far less than if New World screwworm crosses into the United States and we’re forced to fight the pest on U.S. soil.

“We are standing with Secretary Rollins on [the border closure] because she needed to send a very clear signal to the Mexican government that they have not done an effective job of controlling the New World Screwworm, and that they have to step up their game not only in order to protect their producers, but also be a good partner to us and prevent those flies from coming forward. They did not hold up their end of the deal, so she felt that this was a great way to get their attention.”

Secretary Rollins will reexamine the issue in a couple of weeks to see if Mexico has done better, and if they haven’t, she will maintain the suspension at the border to be reviewed monthly thereafter.

“The biggest thing is they just need to cooperate with USDA,” Woodall pointed out. “USDA’s team is well-versed in New World Screwworms, and they know what they are doing. If there was just some more cooperation, we know that it would be a much better way to at least slow down the northern incursion and give us more time to get prepared here in the United States.” That preparation includes the construction of a sterile fly production plant on U.S. soil.

While preventing larger livestock from crossing the border may help slow the spread of NWS onto U.S. soil, any warm-blooded animal can carry the larvae wherever they go, including hawks, deer, rabbits, dogs, and humans.

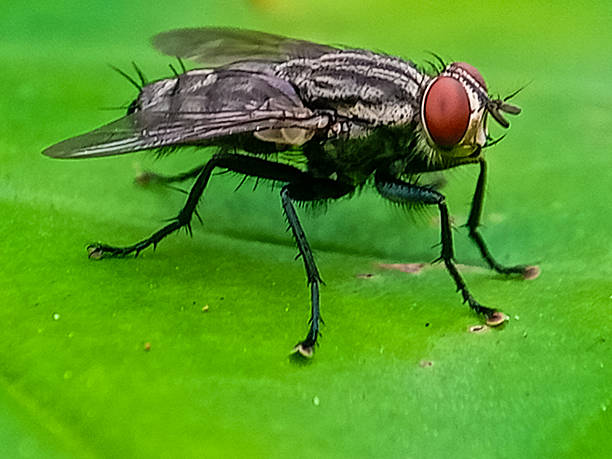

Woodall emphasized that the NWS is not only an issue for cattle. The following rundown of the NWS lifecycle was borrowed from an APHIS information sheet: Screwworm infestations begin when a female fly lays eggs on a wound or orifice of a live warm-blooded animal. Female flies are attracted to the odor of a wound or opening, such as the nasal or eye openings, umbilicus of a newborn, or genitalia. Wounds as small as a tick bite may attract a female to feed. One female can lay up to 3,000 eggs in her lifespan.

Eggs hatch into larvae that burrow into the wound to feed on the living flesh. After about 7 days of feeding, larvae drop to the ground, burrow into the soil, and pupate. The adult screwworm fly emerges from the soil after 7–54 days, depending on temperature and humidity. Female flies mate after 3 days, and males can mate within 24 hours of maturation.

“Untreated, cattle can die within four to seven days,” Woodall stated. “It’s going to be extremely important to help producers understand what they need to be looking for, and give them test kits so they can send those larvae in to determine whether or not they are New World Screwworms and make sure that they understand how to treat those lesions because it is going to be a very key component to our response here as U.S. producers.”

Woodall directed producers to the NCBA website, where many educational resources are already available. The NCBA team will be partnering with Texas & Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association, Oklahoma Cattlemen’s Association, Texas Cattle Feeders Association, and more to ramp up efforts to reach cattle producers in the coming days.

Retrofitting an existing facility to accommodate the production of sterile NWS flies would be the fastest route to get up and going. APHIS has already been searching for such a building, and has a few prospects in mind; however, funding the purchase of the building and the on-going production of the flies is the most imminent hurdle.

“It takes a tremendous amount of resources to be able to produce these sterile flies,” Woodall shared. “The permitting that comes with this is something that is going to have to be expedited. There are a lot of little things with this that you wouldn’t think about until you start looking at the details of what it’s going to take before we can get that first fly produced.”

NCBA continues to call for an expedited permitting process for the sterile fly facility, as once the building is secured, it could still take six months or longer for the building to be ready to begin producing sterile flies.

“That sterile male production is the only effective way that we have to control or eradicate New World Screwworms,” Woodall asserted.

Articles on The Cattle Range are published because of interesting content but don't necessarily reflect the views of The Cattle Range.