Kenny Burdine, University of Kentucky

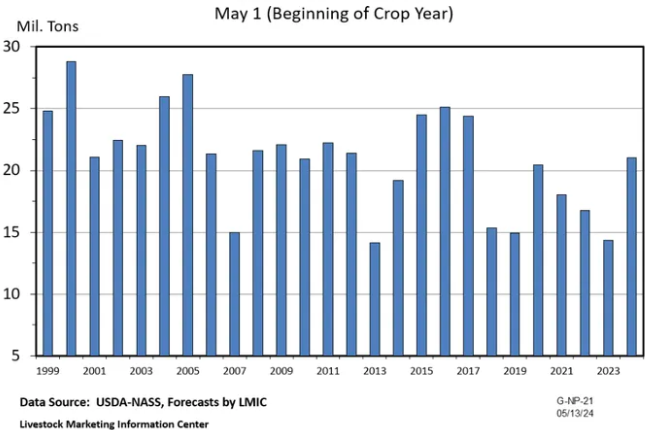

While row crop estimates get the most attention, USDA’s August “Crop Production” report also provides an initial estimate of U.S. hay production and includes projections for individual states. Hay production and stocks have major implications for winter feed supply and winter feed costs for cattle operations. Widespread drought in 2022 led to low hay production levels and left very limited hay supplies coming into 2023. This can be seen in USDA’s May 1 hay stocks figure below. Note that hay stocks in the U.S. on May 1 of last year were at their lowest levels since 2013. A sharp increase can also be seen in 2024 as the larger 2023 crop helped to replenish hay supplies.

Last week’s report suggested increases in production were likely at the national level for both “Alfalfa and Alfalfa Mixes,” as well as “All Other Hay” in 2024. These are the only two categories of hay for which estimates are made by USDA-NASS. In this article, I will focus on the All Other Hay (non-alfalfa) category as that is typically more reflective of hay that is fed to beef cows over the winter. At the national level, non-alfalfa hay production was estimated to be up by 8.1% from 2023, largely due to higher expected yields across the country. While this is encouraging for hay supply in aggregate, hay markets are very localized since transportation costs tend to be very high. This is especially true for large roll bales, which are most often fed by cow-calf operators.

As I have done the last few years, I selected some state estimates from the August report to provide some regional perspective on likely hay production levels. As can be seen in the table below, non-alfalfa hay production is expected to be higher in most states. Texas and Missouri especially stand out and it is worth noting that they are projected to be the two states with the highest production levels nationwide. Oklahoma stands out to the downside, but that decrease is driven by a sizeable drop in expected harvested acres. Hay production was projected higher in Kentucky, Arkansas, and Mississippi, with Tennessee (down 10.2%) being the outlier in the Southeast.

While a lot can still change with respect to hay production this fall, the August “Crop Production” report does paint a picture of increased hay supplies in many areas. In addition to hay production, fall grazing prospects will also impact how much hay will be needed in the upcoming winter. It is also important to understand that these production estimates say nothing about hay quality, which is another important element of the discussion. I like to examine hay production estimates and do think it provides some general perspective, but I would also reiterate how different hay availability can be across the country. It’s never too early to think about winter hay needs and make plans to source additional hay, if needed.