Consumer borrowing costs in the U.S. have skyrocketed, but the CPI hasn’t counted interest rates since 1983.

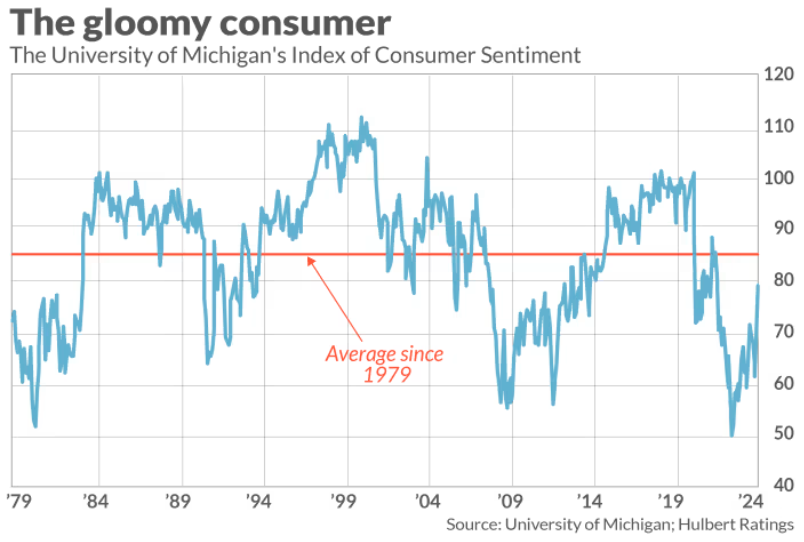

There are widely divergent perspectives between Wall Street, where exuberance has led the U.S. stock market to all-time highs, and Main Street, where the average American continues to be decidedly gloomy. I argued earlier this year that this ”Wall Street-Main Street” disconnect is not healthy, either for the stock market in particular or for the U.S. economy as a whole.

Some of you responded that the disconnect is artificial, since it exists only because consumers are being irrational. If consumers were rational, this argument goes, they would be happy and consumer sentiment measures would be soaring. After all, U.S. unemployment is close to a 50-year low and the 12-month inflation rate is one-third as high as it was two years ago.

A new study takes exception to this anti-consumer narrative, finding that consumers are entirely justified in their gloominess. If inflation were measured correctly, the researchers argue, then it would be evident just how much consumers are hurting.

Entitled “The Cost of Money is Part of the Cost of Living: New Evidence on the Consumer Sentiment Anomaly,” the study was conducted by Marijn Bolhuis of the International Money Fund and Judd Cramer, Karl Oskar Schulz, and Lawrence Summers, all of Harvard University, the latter the former Treasury secretary. The “anomaly” in their title is the unusually gloomy consumer.

The researchers find a strong historical correlation between changes in the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index and consumer borrowing costs. Yet the consumer price index, or CPI, doesn’t fully reflect those costs, they argue. If it did, then the consumers’ gloominess would be seen as entirely rational.

That’s because consumer borrowing costs in the U.S. have skyrocketed over the last couple of years. Interest rates — whether on credit-card debt, car loans, or mortgages — are higher than they’ve been in decades. Particularly revealing is a cost-of-housing index the authors calculated by taking into account both the mortgage rate and the average cost of a home. They find that the cost of housing in the U.S. has more than doubled since the pandemic, in contrast to the CPI, which has increased by around 20% over the same period.

The authors calculate that had the CPI fully reflected higher borrowing costs, it would have peaked at 18% in November 2022 and still be around 8%.

So there’s no mystery — no “anomaly” to explain — in why sentiment has been, and remains, below average. If there is an “anomaly” that needs explanation, it isn’t the gloomy consumer — it’s the exuberant stock market.

So, if the Wall Street-Main Street disconnect does get resolved any time soon, that will more likely happen by the stock market falling rather than the consumer becoming giddy.

The CPI used to reflect borrowing costs

There is an interesting footnote to this discussion: The consumer price index up until 1983 included consumer borrowing costs. According to the researchers, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reflected these costs by “taking house prices, mortgage interest rates, property taxes and insurance, and maintenance costs as inputs.”

The researchers acknowledge that this approach led the BLS to overstate true inflation. But the solution that went into effect after 1983 may have gone too far in the other direction: “Mortgage costs are a decisive factor in consumers’ assessment of their ability to make what for many Americans amounts to the most meaningful purchase of their lives. The exclusion of these costs means that the current methodology excludes a central part of consumers’ financial well-being.”

Source: Mark Hulbert -- MarketWatch