Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University

The January Cattle report from USDA-NASS has included the inventory of beef replacement heifers since 1920. The latest USDA Cattle report pegged the January 1, 2024 beef replacement heifer inventory of 4.86 million head, down 1.4 percent year over year. However, the latest report revised the initial estimates of the 2023 inventory from 5.16 million head down to 4.93 million head. This means that the 2024 beef replacement heifer total is down 11.4 percent from 2022. With the revisions, the 2023 inventory, along with the 2024 beef replacement heifer inventory are below 5 million head and are the smallest January 1 inventories since 1950.

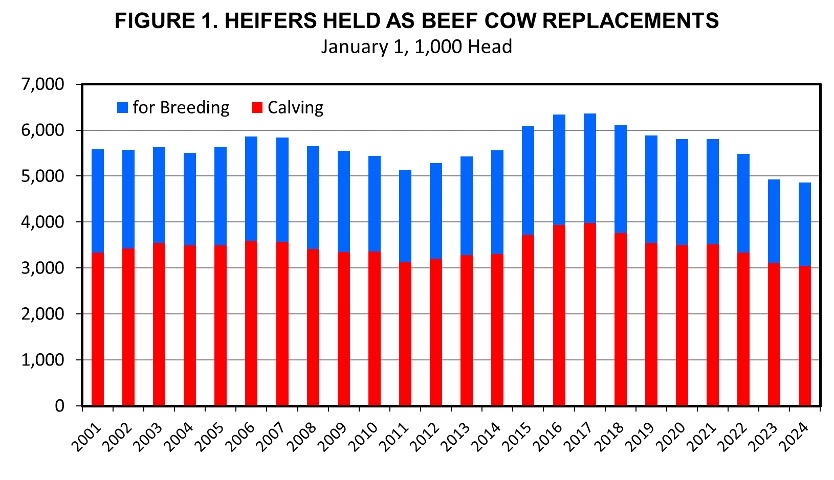

Since 2001, USDA has provided an additional breakdown of beef replacement heifers into the number expected to calve (bred heifers) and the residual of heifers retained for breeding. This emphasizes that the replacement heifer total consists of heifers from two different calf crops: coming two-year-olds that will calve this year and yearling heifers, from last year, in development for breeding (See Figure 1 above).

The average number of beef heifers calving since 2001 has been 3.46 million head, an average of 11.1 percent of the beef cow inventory. This compares to the average herd culling rate (beef cow slaughter as a percent of the beef cow inventory) of 10.0 percent over the same period. Year by year the relative percentages of heifers calving and cow culling determines whether the beef cow herd increases or decreases. The inventory of bred heifers for 2024 is the smallest in data available since 2001.

Yearling heifers saved for breeding this year become bred heifers next year. However, on average, the calculated yearling heifer total is only 64 percent of the bred heifer total for the following year. The remaining 36 percent of bred heifers is assumed to be impromptu heifer breeding in the previous year in which producers decide to breed heifers not previously identified as replacement heifers. These extra heifers bred are presumed to be sourced from the other heifer inventory. This means that planned heifer breeding accounts for roughly two-thirds of heifers calving with the remaining one-third the result of impulse (unplanned) heifer breeding (See Figure 2 below).

Not surprisingly, impulse heifer breeding is more variable than planned heifer breeding. Statistically, impulse heifer breeding is about 80 percent more variable than planned heifer breeding. Therefore, impulse heifer breeding plays an important role in the dynamics of cattle cycles. For example, in the cyclical herd expansion from 2014 to 2019, impulse heifer breeding was the first to expand, increasing in 2014 by three times more than planned heifer breeding. As herd expansion slowed near the 2019 peak, impulse heifer breeding decrease first and more rapidly compared to planned heifer breeding. The data available now allows a more detailed accounting of heifer breeding and quantifies commonly described behavior when producers decide to increase or decrease heifer breeding in an impromptu manner.

The 2024 inventory of bred heifers is down 1.9 percent year over year and consists of yearling heifers bred last year, which was down 15.1 percent year over year and a 27.3 percent increase in extra heifers bred (impulse breeding). In other words, while planned heifer breeding decreased to a record low level (data back to 2001), impulse breeding of heifers increased sharply in 2023, nearly offsetting the decrease in planned heifer breeding. Is this increase in impulse heifer breeding the first sign of industry attempts to begin herd expansion? Maybe…although it is not clear yet. When both planned and unplanned heifer breeding are increasing it will be more certain what producers’ intentions are. It will depend on evolving producer expectations as well as weather that will determine what is possible in 2024 and beyond. Stay tuned.