Cattle that recover from initial infection become carriers for life.

By Rosslyn Biggs, DVM, Oklahoma State Extension

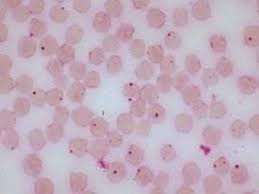

Bovine anaplasmosis is caused by the rickettsial bacteria, Anaplasma marginale. It invades the red blood cells leading to early signs such as fever, anemia, pale mucous membranes, weakness, and loss of appetite. As the disease progresses, excitement, jaundice, incoordination, and death may be seen. Abortions and retained placentas may also increase. It typically takes four to eight weeks following the date of infection for signs to become evident. Signs are most severe in animals greater than two years of age although cattle may be infected at any age.

Cattle that recover from initial infection become carriers for life. Carrier animals typically do not show clinical signs and serve as a source of infection for unexposed cattle. However, carrier animals under times of significant stress, such as pregnancy, can revert to exhibiting clinical signs.

Transmission primarily occurs through ticks and biting flies. Wildlife with infected ticks can also play a role in spreading the disease as they travel, transporting the ticks with them. Infected cows may also transmit the agent to their unborn calves. Equipment contaminated with infected blood, such as injection needles used on multiple animals is another common mechanism to transmit the bacteria. Diagnosis is through blood testing.

Oxytetracycline and chlortetracycline are approved for control of the agent and enrofloxacin is labeled to treat initial infections in certain classes of beef cattle. Other supportive treatments may also be needed. There are currently no approved antimicrobials in the U.S. labeled to eliminate the anaplasmosis carrier status.

With limited options to address the disease, pharmaceutical stewardship must be considered when reaching for antimicrobials used in the treatment and control of anaplasmosis to maintain long term effectiveness of these products. There are currently no commercially available USDA approved vaccines for anaplasmosis. In some states, conditionally approved vaccines may be obtained. These vaccines may prevent anaplasmosis related deaths but do not prevent infected cattle from becoming carriers and are not protective against all anaplasmosis strains.

Determining herd anaplasmosis status is important to developing an approach. Testing of new introductions prior to purchase or turnout is also recommended especially if animals are sourced from areas not known to be endemic for anaplasmosis. Other biosecurity measures include maintaining a closed herd and preventing reuse of contaminated equipment during processing. Producers should consult with their veterinarian regarding the best approach for treatment and control specific to their operation.