American Farm Bureau Federation

Chances are, when you think of the West, images of cattle and horses and the ranchers that manage them are top of mind. For centuries, grazing livestock have been at the heart of rural economies across what is now the Western United States. Through these many generations, ranchers have contributed far more than their job titles indicate. They are county commissioners, teachers, bankers, truck drivers, energy workers, hunters, sportsmen and more – contributing directly to the stability and longevity of the communities in which they live. This article reviews the latest available economic metrics evaluating both direct and indirect benefits of livestock grazing on federally owned lands.

Background

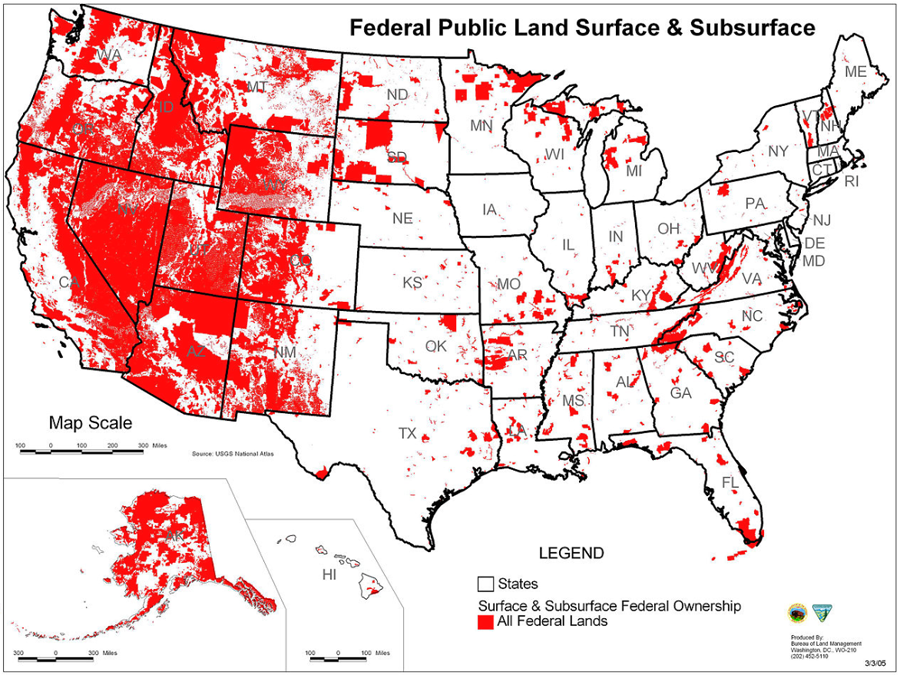

The federal government owns roughly 640 million acres of the 2.27 billion acres of land in the United States – just over 28% of total land. The percentage of federally owned land in each state varies widely, from 0.3% in Connecticut and Iowa to nearly 80% in Nevada. Federal ownership of land is heavily concentrated in the West with 61.3% of Alaska federally owned, along with 46.5% of the 11 next westernmost states. In comparison, the federal government owns 4.2% of land in the remaining 38 states. Five major federal agencies administer 620 million acres of federally owned land, led by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) at 248.3 million acres, Forest Service (FS) at 193 million acres, Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) at over 90 million acres, the National Park Service (NPS) at 80 million acres, and Department of Defense (DOD) at just over 11 million acres. Residents of heavily federally owned states that utilize lands for commerce have to abide by these federal agencies’ regulations – a challenge much of the rest of the country does not encounter.

Agencies administer permits that allow ranchers to graze livestock on specified public lands for a fee. Grazing fees through BLM, in 2023, for example, cannot fall below $1.35 per animal unit month (AUM) and any fee increase or decrease cannot exceed 25% of the previous year’s levels. An AUM is the amount of forage needed to sustain one cow and her calf or one horse, or five sheep or goats for a month. Actively permitted AUMs in 2022 ranged from a low of 254 in South Dakota to 2.1 million in Nevada, with a total of 10.8 million across the country. Active permits ranged from four in Oklahoma to 3,813 in Montana, with a national total of 17,911. Any U.S. citizen or validly licensed business can apply for a BLM grazing permit if they buy or control private property, known as a base property, that has been legally recognized as having preference for use of public lands grazing or acquire property that can serve as a base property and then apply to BLM to transfer a grazing preference from an existing property to the acquired property. There are different types of permits, the most common being the term permit, which may be issued for up to 10 years. Term permits describe the season of use, number of AUMs authorized and the kind and class of livestock that can be grazed on a specified area of federal lands. Temporary permits may be issued for a period not to exceed one year and are sparingly used. Livestock use permits are issued for a primary use other than grazing livestock for a year or less and are commonly used in research circumstances.

The Congressional Research Service reported that of the 248 million acres administered by the BLM, 154 million acres (62%) are available for grazing, though only 139 million acres (56%) are in use. Of the 193 million acres managed by the FS, more than 95 million acres are available for grazing (49%) and 77 million (40%) are actively grazed. There is also some grazing on NPS land, though this number is comparatively small. Of the approximately 640 million acres of federally owned land, about 35% is actively permitted for grazing purposes.

Direct Effects

In this analysis, “direct effects” refers to the portion of monetary value of livestock sales linked to forage produced and utilized on public lands. Typically, ranching of cattle, sheep and goats uses a combination of private and public grazing lands, as well as grazed forage and purchased forage and/or grain. This means that while a finished steer that ultimately ends up at market somewhere in the Midwest may have started on public lands forage, many other sources of forage contributed to its final market weight. In a recent study by the U.S. Forest Service, researchers focused on quantifying economic contributions of federal grazing at the state and national level by adjusting sales values reported by the census of agriculture by active AUM numbers. This methodology allows us to estimate the value of end livestock sales directly attributable to public lands forage. Figure 2 displays the combined value of cattle, sheep and goat sales linked to public lands grazing. In total, over $1 billion in livestock sales value is attributable to public lands forage. States like New Mexico, Wyoming, Idaho and Montana all come in at over $100 million each. The small values calculated for some Eastern states is linked to small cattle grazing allotments under the FS. NPS grazing was not estimated.

Figure 3 break, down these direct estimations further. Figure 3 displays the value of cattle sales attributed to public lands forage. Close to 90% of the estimated total livestock value, or $893 million, is linked to cattle production. Idaho ($122 million), New Mexico ($119 million) and Wyoming ($100 million) are the top public lands cattle states. These direct sales values contribute to the income basis for thousands of rural families in these states. Economic modeling specific to Idaho, Oregon and Nevada showed the loss of 5,389 active grazing permits resulted in an average 60% decline in cattle sales, 50% decline in labor income, a 65% decline in personal income (from $33,940 to $11,812), per operation, and billions in downstream economic losses. Additionally, the tax revenue received on these sales supports public safety, education and infrastructure in locations that are often already underserved and don’t otherwise receive tax revenue from federally-owned land.