Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University

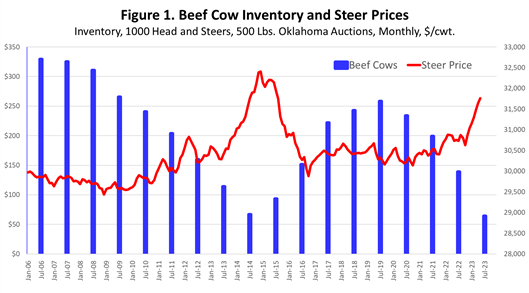

For the second time in a decade, drought has pushed cattle numbers in the U.S. lower than planned and lower than needed to meet the demands of the market. Figure 1 above shows how the current situation is similar to the beginning of the previous low in beef cow numbers.

Cattle prices are trending higher, starting to increase much as they did in 2013 prior to the herd rebuilding that commenced in 2014. However, while drought has diminished in much of the country, important beef cattle regions in the central and southern plains that are still in drought limit how the cattle industry is able to respond. Beef cow slaughter is falling so far this year, usually the first sign of ending liquidation and stabilizing the cow herd. However, with the year more than one-third over, cow slaughter is down about 11 percent year over year and that is not enough of a decrease to ensure the end of herd liquidation. In 2014, beef cow slaughter dropped just over 18 percent from the previous year to put the brakes on herd liquidation. I suspect that the ongoing drought is masking continued liquidation in some areas up to this point. While signs are encouraging that the drought will continue to fade through the year, more beef cow herd liquidation is likely in 2023.

The supply of bred heifers on January 1 was down 5.1 percent year over year to the lowest inventory since 2011. The low bred heifer inventory combined with the relatively slow reduction in beef cow slaughter makes additional beef cow herd liquidation this year probably unavoidable. In other words, if drought conditions continue to improve, 2024 will probably be the low point of the herd similarly to 2014, albeit at even lower beef cow inventories. The peak in cattle prices in 2014, extending into 2015, precipitated record heifer retention in 2015 and 2016 that pushed the beef cow herd higher.

The supply of replacement heifer calves (available to be bred this year) on January 1 was very low, suggesting that the ability to add heifers next year may be limited. However, some heifers not reported as replacements typically get bred and that number may increase this year. Nevertheless, the overall supply of heifers remains limited. The inventory of heifers in feedlots remains high, though it is declining. Thus far, heifer slaughter in 2023 is fractionally higher year over year on top of the large heifer slaughter level last year. Heifer slaughter in 2022 was 30.6 percent of total cattle slaughter, the highest proportion since 2005. Heifer slaughter is expected to decrease through the year but, like beef cow slaughter, at a relatively slow rate. What all of this means is that heifer retention likely will begin in earnest this fall with heifer calves to be bred in 2024. Modest herd expansion is possible next year with faster herd expansion after 2024.