MarketWatch

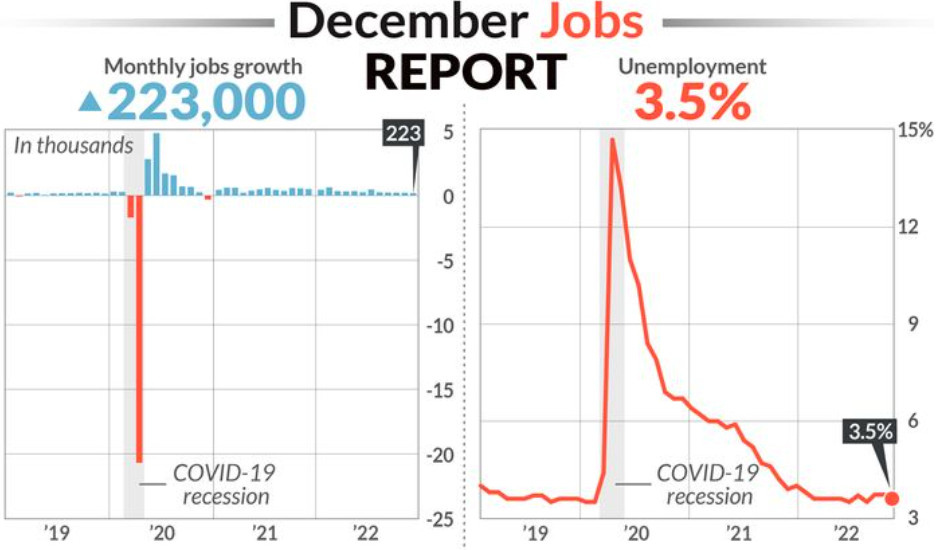

The numbers: The U.S. generated 223,000 new jobs in December to mark the smallest increase in two years, but the labor market still showed surprising vigor even as the economy faced rising headwinds.

The unemployment rate, meanwhile, slipped to 3.5% from 3.6%, the government said Friday.

The jobless rate has touched 3.5% several times since 2019, matching the lowest level since 1969.

One good sign for Wall Street and the Federal Reserve: Hourly pay rose a modest 0.3% last month, suggesting wages are coming off a boil.

The increase in wages over the past year also slowed to 4.6% from 4.8%, marking the smallest gain since the summer of 2021.

U.S. stocks DJIA, 1.56% SPX, 1.54% rose in premarket trades and bond yields edged higher after the report.

Economists polled by The Wall Street Journal had forecast a smaller increase in new jobs of 200,000.

The resilient labor market is a double-edged sword for the Federal Reserve.

For one thing, a scarcity of workers has driven up wages and threatens to prolong a bout of high inflation. The Fed wants the labor market to cool off further to ease the upward pressure on prices.

The strong labor market also offers the best hope for the Fed to avert a recession as it jacks up interest rates to the highest level in years. Higher rates reduce inflation by slowing the economy, but if most people are working, they are likely to spend enough to keep the economy afloat.

James Bullard, president of the St. Louis Federal Reserve, said on Thursday the odds of so-called soft landing have gone up in part because of the sturdy labor market. He was referring to a Goldilocks scenario of sorts in which the central bank vanquishes inflation without causing a recession.

Senior Fed officials still want to see the jobs market slacken some more, however. They are likely to keep raising rates — and keep them high — until demand for labor, goods and services ease up.

Big picture: The U.S. economy has shown more fragility, especially in segments like housing and manufacturing that are sensitive to high interest rates. Many economists predict a recession is likely this year due to the higher cost of borrowing.

The Fed, for its part, is trying to thread the needle: Bring down high inflation and keep the economy out of recession.

Whatever the outcome, one thing is virtually certain: The unemployment rate is expected to rise as U.S. growth wanes. Whether it’s enough to help the Fed achieve is far from clear.

Key details: Health care providers, hotels and restaurants accounted for most of the increase in employment last month. They added a combined 150,000-plus jobs.

Hiring was weaker in most other sectors, suggesting that the labor market is likely to soften further.

High-tech has been hit particularly hard and is experiencing a wave of layoffs.

Employment in so-called professional businesses, which includes some tech, fell by 6,000, largely reflecting fewer temps being hired. It was the only major category to post a decline.

The share of working-age people in the labor force — known as the participation rate — rose a tick to 62.3%.

It’s still below pre-pandemic levels, however. A lack of people looking for work is a chief source of the labor shortage.

Hiring in November and October was little changed after government revisions. The economy added 256,000 jobs in November and 263,000 in October.

Looking ahead: “Job growth remains strong, but it’s clearly slowing,” said chief economist John Leer of Morning Consult.

“The U.S. jobs report had a little something for everyone: plenty more jobs and better job prospects for the unemployed, but also somewhat slower wage growth and a pullback in work hours that suggests the economy is losing steam,” said senior economist Sal Guatieri of BMO Capital Markets. “Alas, a hawkish Fed will likely fret more about the ongoing tightness in labor markets,” he added.

Investors worry a strong labor market will push the Fed to take sterner measures to slow the economy. The slowdown in hiring and wage growth is likely to be seen in a positive light.