The Daily Yonder - Claire Carlson

Farm advocates say that record-breaking fertilizer prices are decimating farmer profits and pulling wealth out of rural communities for the benefit of a handful of corporations that control the market.

Groups such as Farm Action are calling on the federal government to enforce antitrust laws against the small number of fertilizer manufacturers that remain in the industry.

“These companies came into [rural communities] through acquisitions and mergers and are extracting all of the money in that food chain, leaving nothing behind for the community,” said Joe Maxwell, president of Farm Action and former lieutenant governor of Missouri. “It bankrupts farmers.”

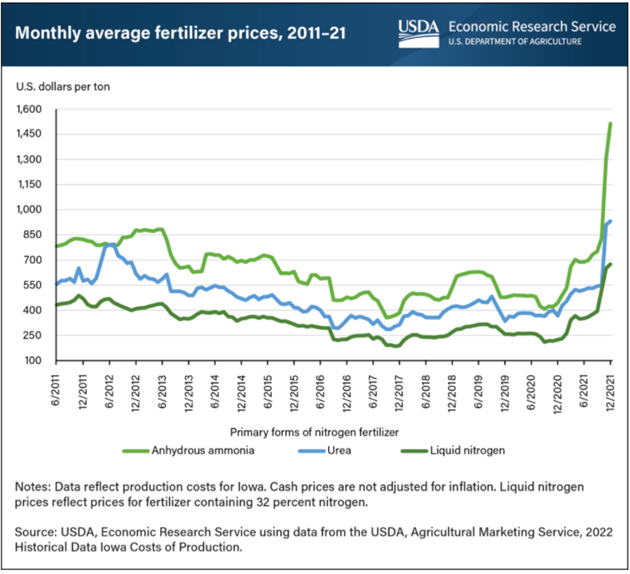

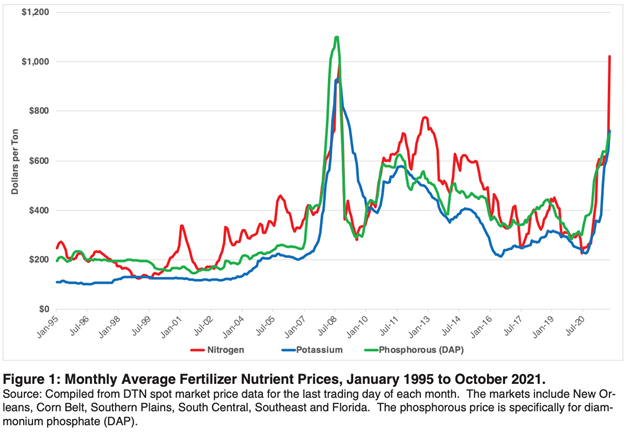

Prices for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilizers – the three most commonly used commercial fertilizers – more than doubled between 2020 and 2021, according to data from Texas A&M University. Nitrogen fertilizer, which accounts for more than 50% of the commercial fertilizer used by farmers, is expected to see price increases in 2022 of more than 80% from the previous year.

The cost of fertilizer is going up, but crop prices aren’t, said Nate Kauffman, Omaha branch executive of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Food processing companies aren’t paying more for crops, and consumer prices have been steady. That leaves farmers to absorb the higher fertilizer costs, which already is a major expense for farmers.

The fertilizer industry blames the price increases in natural gas – used to make nitrogen fertilizer – and supply chain issues due to Covid-19. Farmer advocates disagree.

“When we only use basic supply and demand economic modeling, it doesn’t tell the whole story or give a clear understanding to the larger dynamics when the market is so heavily concentrated,” Maxwell said.

Four corporations supply 75% of the nitrogen fertilizer in the U.S.: CF Industries, Nutrien, Koch, and Yara-USA. Two corporations supply all of North America’s potash, a potassium-based fertilizer: Nutrien Limited and the Mosaic Company. Between 1980 and the mid-2000s, the number of fertilizer producers for the U.S. dropped from 46 to 13 firms, according to Farm Action.

Farmer advocates worry that the small number of manufacturers means they have power to raise prices without fear of losing customers to competitors.

“Competition was abandoned when these mergers were allowed to occur,” Maxwell said. “The concentration allows a company to say that if the farmer makes more, we’re going to make more, we’re going to take that out of the farmer’s pocket and out of the rural community.”

Source: https://afpc.tamu.edu/research/publications/files/711/BP-22-01-Fertilizer.pdf

Antitrust laws have a long history in American politics. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was the first to prohibit monopolies and was strengthened by the 1914 passage of the Clayton Antitrust Act, which banned anti-competitive mergers. The Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 assures fair competition and trade practices.

Farm Action believes that the actions of the fertilizer industry violate these laws. The organization sent a letter to the Department of Justice in December 2021 asking them to investigate fertilizer-market manipulation. Several other farmer representative groups submitted testimony highlighting the issue at a House Committee Judiciary hearing in January. These groups are calling for better enforcement of antitrust laws.

An agricultural economist says having fewer producers does not necessarily lead to higher prices.

“You have to be very cautious about equating the number of firms with the existence of market power,” said Carl Zulauf, professor emeritus in agricultural economics at The Ohio State University.

Price competition can exist even with a small number of firms operating in the market, Zulauf said. Market power, or monopoly power, isn’t necessarily a concern as long as other fertilizer manufacturers can enter the market easily.

“I’m not disputing that there isn’t concentration relative to what it was 20 years ago,” Zulauf said. “I’m just saying you’ve got to ask some important questions [about competition] before you can conclude that yes, there is market power because there are fewer firms.”

Kauffman with the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City said economists are also paying close attention to the war in Ukraine’s effect on fertilizer prices.

“Combined, Russia and Ukraine account for a pretty large share of the production of things like natural gas and some fertilizers, as well as a large global share of wheat production,” he said. Changes to commodity prices and input costs in the coming months will show the full effects of the conflict, according to Kauffman.

Whatever the causes, higher fertilizer prices will affect how farmers grow their crops. Farmers could switch to crops that need less fertilizer or use a “split fertilizer” strategy, which times fertilizer application to when crops are most capable of absorbing nutrients, according to Zulauf. Other strategies include crop breeding and regenerative agriculture, but these options take time. Whether prices remain high will determine the long-term strategies farmers use to decrease fertilizer dependency.

“We’ve got to change our practices for the environment, for our planet, and for our pocketbook,” Maxwell said.

Even with these different practices, Maxwell said, some amount of fertilizer will still be essential to crop production.

“Everybody needs to understand that farmers need fertilizer,” Maxwell said. “This is a national food security issue. It’s complex, but its complexity should not stop us and our government from going after these companies.”