Scott Brown - University of Missouri Livestock Economist

With 2022 set to be the third consecutive year of declining beef cow inventories, and the fourth year with a smaller calf crop, beef production is expected to retreat by about 3% in the next year.

Potential developments in the ongoing drought situation place a range of uncertainty around this estimate. However, it is almost assured that U.S. beef production will be on the decline into the medium term. While this bodes well for cattle price projections, it could return consumers to a situation last experienced about a decade ago, when international consumers were willing to pay up for beef to the point that availability for the domestic market was compromised.

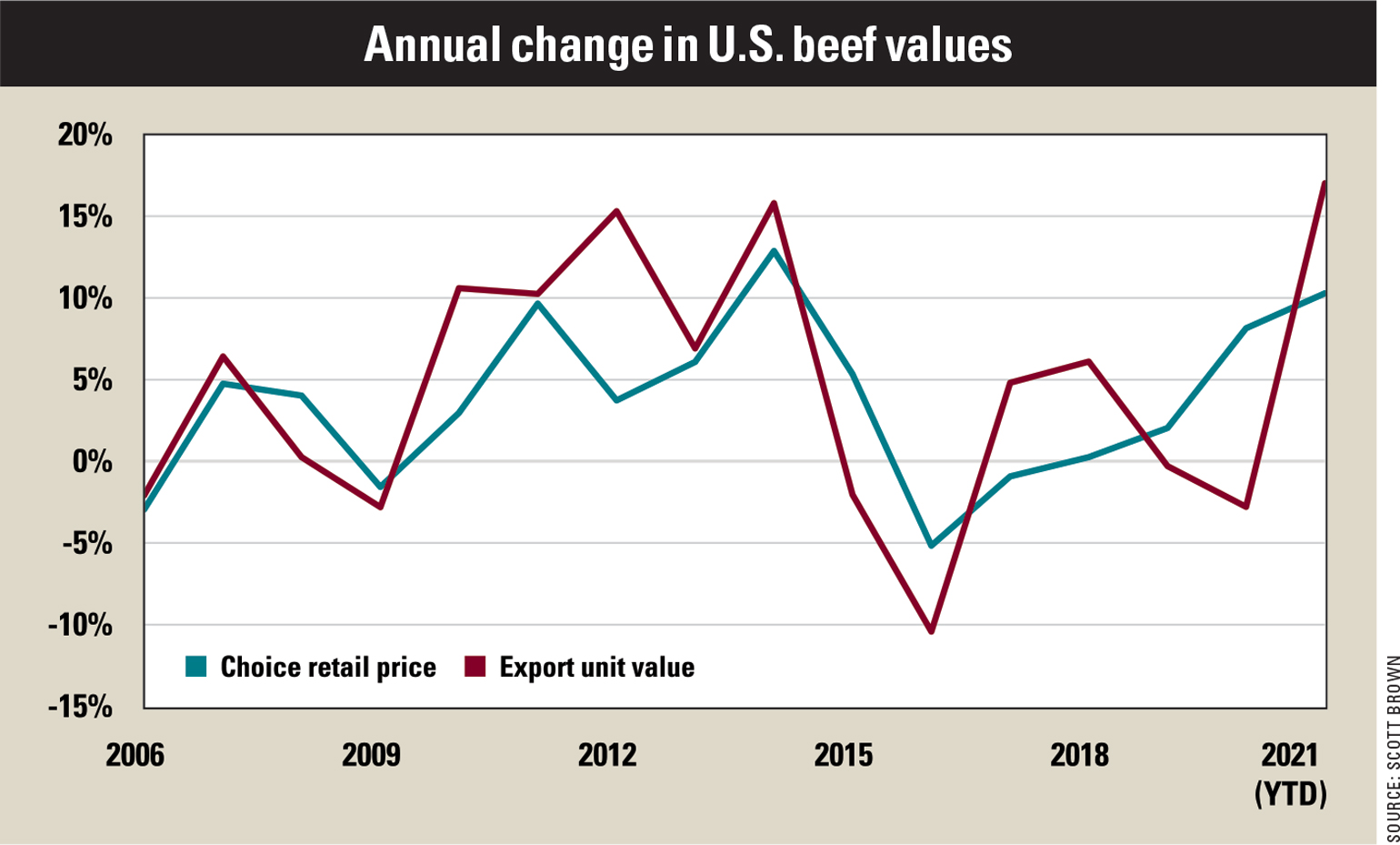

From 2009-11, beef exports grew by 850 million pounds, while domestic per capita beef availability declined by more than 6%. This was also a period of history when the growth in beef export values was outpacing domestic retail price growth, as international beef buyers were essentially outbidding retailers for product and taking it out of the U.S.

Beef in demand

You may think U.S. retail beef prices are high, and no one will argue that fact in absolute terms. Choice retail beef prices have topped $7.85 per pound for each of the past three months — 24% above year-ago levels. But the average export value of U.S. beef grew at an even faster clip in 2021.

The average beef export value for October was 37% higher than year ago, with the year-to-date average export value up 17%. And upward pressure very well could remain in place for the next few years.

Most of the major beef export markets in Asia have seen values increase similarly to the total, with unit export values to Mexico much elevated at 54% higher in October (29% year to date) and those to Canada trailing the average — up only 22% in October and 8% for year to date.

Production decisions

While it is certainly not a bad situation to have customers in all parts of the world clamoring for your product, given the length of time that it takes from when individual cattle producers decide to build up their herds until this decision actually flows into increased national beef production, the industry could be heading for a period of years where U.S. beef availability could be limited.

That’s particularly true if drought conditions spread or worsen, and producers have no choice but to continue to liquidate the herd because of a lack of sufficient forage supplies.

The long existing presence of the U.S. cattle cycle makes it extremely likely that a few years down the road, beef production will again be growing and producers will need to find a profitable home for the additional beef.

As prices continue to move higher in the years to come, let’s hope that not too many U.S. consumers move away from beef and lose their appetite for the quality products being supplied by the cattle industry.

Brown is a livestock economist with the University of Missouri. He grew up on a diversified farm in northwest Missouri.