Katelyn McCullock, Livestock Marketing Information Center director

The U.S. is in its second year of market-affecting drought, particularly for the Western U.S. and the Northern Plains. The situation is severe enough that early weaning and liquidation decisions will actively be made for the cow herd this summer and fall.

The market impact of those decisions will likely be felt in the form of depressed cull cow values, and a more stretched placement pattern in cattle on feed. Next year and 2023 will likely see the majority of impacts for feeder cattle and fed cattle pricing patterns.

Liquidation factors:

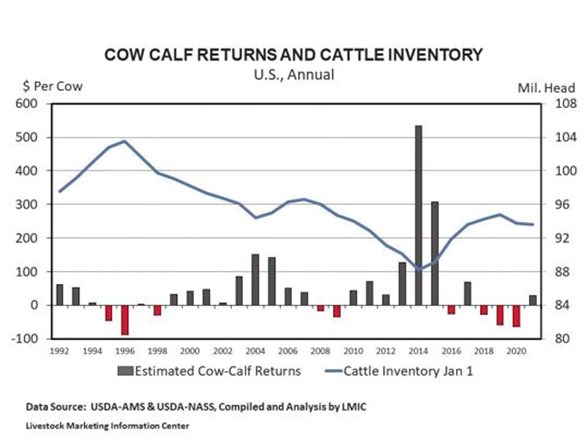

The drought has already shown it is having an impact on the U.S. cattle herd. The July 1 Cattle Inventory report was released by the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) at the end of July. It reported beef cow numbers are already 2 percent (650,000 head) down, brought on by about a 9 percent increase in beef cow slaughter that took place from January through June. The majority of those culling decisions appear to be a result of deteriorating drought conditions combined with expensive and tight feed supplies.

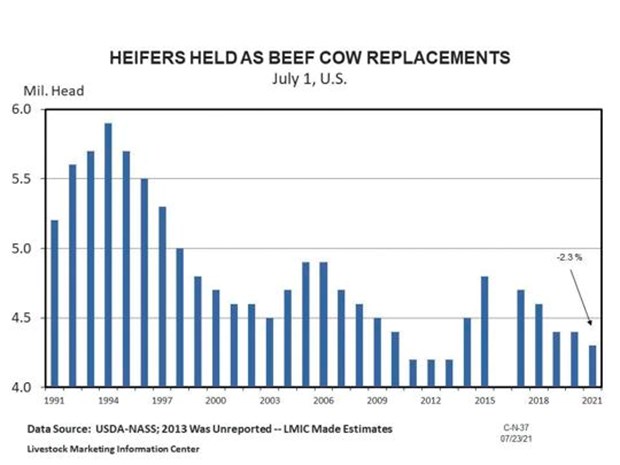

This not only has led to cow liquidation, but producers appear to be shying away from retaining heifers. The July 1 Inventory report noted that beef heifer replacement numbers were down by 2.2 percent, or 100,000 head.

Cattle on feed also showed the number of heifers in feedlots has maintained a larger percentage than what we might have expected had this liquidation phase not picked up its pace. On July 1, heifers were estimated at about 38 percent of the total steers and heifers on feed.

These July 1 Cattle Inventory numbers are subject to revision, but they point to important themes in the industry. The first is that carrying capacity on pasture and range in the first half of the year, in combination with high feed costs, was not economical for cattle producers to hold cows. The lack of heifer retention suggests that this is not a refreshing of the herd, but one where reduced cow numbers are likely to continue through the remainder of 2021.

The last two years’ high numbers of beef cows have moved to slaughter in the fourth quarter. This may be true again in 2021, and implies the Jan. 1 beef cow number is even smaller than July.

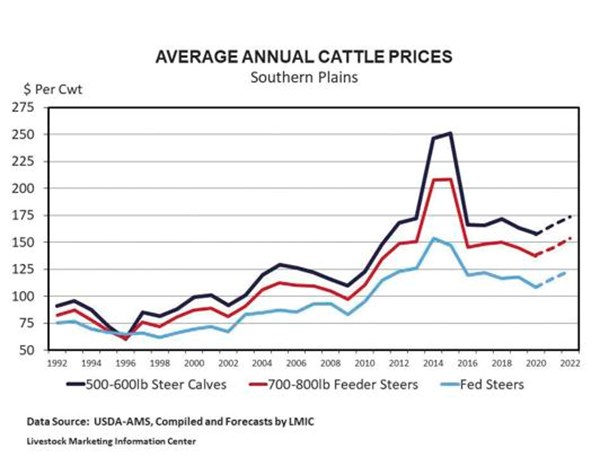

The trajectory points towards smaller cattle supplies at least through 2023. That in turn is expected to push up feeder cattle prices and fed cattle prices. The Livestock Marketing Information Center (LMIC) is estimating gains in the feeder cattle complex will rise 5-7 percent in 2022 over 2021 on annual average basis, and in 2023 those prices are expected to climb again year over year. Fed cattle prices could climb even more dramatically.

Demand patterns:

One of the bigger wild cards for 2021 has been the demand profile, the reemergence of restaurant traffic and a booming export market. All those factors have supported boxed beef cutout values, and helped fed cattle prices stay elevated despite still-slower chain speeds at slaughter plants through most of 2021.

The pulls from those two situations are both largely attributed to a post-pandemic boom, and are not expected to remain, at least at the current level into 2022.

For example, LMIC has raised its export forecast to over 10 percent year over year in 2021, a new record high. Through the first half of the year, exports have been well above that forecast. However, if these influences waiver, as another COVID-19 variant spreads, or supply chains normalize, exports could fall to more normal gains in the second half of the year.

Additionally, the year-over-year comparisons are paralleled to the large declines in 2020. LMIC expects 2022 exports to pull back slightly.

The domestic consumer demand profile also has uncertainty with respect to long-term trends and current demand structure. A large portion of restaurants shuttered their doors last year and will not return.

Though, the reopening of restaurants has caused a surge in wholesale beef products that fit food service needs. Americans pre-COVID consumed about 50 percent of food outside the home.

Those shifts are not expected to return immediately, particularly when food inflation, and market fundamentals have pushed retail beef prices close to record-high levels. The consumer is expected to still be cautious on the economic front, and high savings rates may help soften the blow to demand we would typically expect when beef prices rise.

Additional factors:

There are still many aspects of the meat complex, COVID-19, the U.S. economy and the world that are unknown and influencing what has been a rather volatile market for the last year and a half. The expectation is that some of these ripple effects may not subside, but they may become more predictable. Cattle prices are expected to experience less volatility in the second half of 2021 and in 2022 and adhere to normal seasonal trends.

Even with the possibility of more COVID variants, expectations are that we as a global population are better prepared than we were the first time around. That should help some of the effects to be mitigated, should we have another severe outbreak. COVID-19 is not expected to be the dominant driver that it was in 2020 and the beginning of 2021.

Fundamentals, and primarily a sharp liquidation in the U.S. beef cow herd, are more likely to be the key drivers, as well as feed costs and the potential for drought continuation. Hay prices are unlikely to move lower in 2021 or in 2022 as acres have been reported lower in June. This will likely continue the liquidation phase in certain areas of the country because the feedstuffs required will not be available or it may not be cost-effective to winter cows into 2022.

Those producers that do have the ability to hold cows will very likely benefit from a strong run-up in calf prices. LMIC is projecting cow-calf returns to continue to increase in 2022 and 2023 and could trigger a bottom in the cattle cycle, though it is unlikely to see any year-over-year growth in beef cows before 2024.