Paul Beck, Oklahoma State University Extension Beef Cattle Nutrition Specialist

Drought is a possibility in all climates and environments. When I was in Arkansas, the driest year on record for my location was right at 30 inches of rain in 2012. This would seem to be a pretty good year in central and western Oklahoma, but was tragic when considering this was a 40 to 50% reduction from average. When everything is stocked for 55 inches of rain, 30 inches in a year seems to be an insurmountable obstacle.

Flexible stocking is a drought-prep strategy used for hundreds of years that seems to have gone out of favor over the last few decades. If 25 to 30% of the ranch is dedicated to retained or purchased stocker calves or retaining high quality heifers for resale each year, profitability of the ranch can be improved during the good years by adding value to the calves; but when drought conditions occur these calves are easily sold. This allows the cowherd to be spread over more acres and will keep drastic culling and herd liquidation from being forced on you.

Grazing management is always a good idea, one of the benefits of rotational grazing is to give the most preferred plants in a pasture rest and recovery from grazing. As preferred plants are repeatedly grazed root growth can be negatively impacted, top-growth is a reflection of root-growth so with repeated grazing roots get shallower. This decreases the forage plant’s ability to reach water and reduces competitiveness with deeper rooted weed species. Also, there is reduced surface residue which decreases water infiltration and increases soil surface temperature. Overgrazed pastures are at more risk during a drought and in severely overgrazed pastures drought conditions may be caused as much by poor grazing management as the weather conditions.

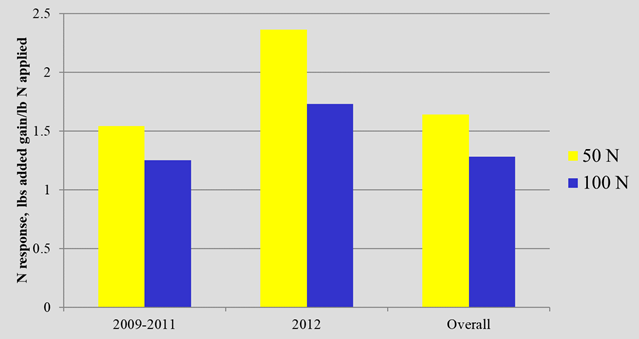

In introduced forage species like bermudagrass, tall fescue or old-world bluestems, fertilization improves water used efficiency. This is shown in an experiment with stocker calves grazing bermudagrass pastures that were unfertilized or fertilized at 50 pounds of actual N/ acre (150 pounds of ammonium nitrate/acre) or 100 pounds of actual N/acre (300 pounds of ammonium nitrate/acre). During the “normal” rainfall years from 2009 to 2011 (Figure 1) each pound of fertilizer applied to pastures increased steer gains per acre by 1.5 pounds (at 50 pounds of actual N) and 1.25 pounds at the 100 pounds of N per acre rate. But during the severe drought year of 2012, steer gains were increased by 2.4 pounds/acre for each pound of N applied at the 50 unit of N rate and were increased by 1.7 pounds/acre at the 100 unit of N rate. The unfertilized pastures were affected more by the drought stress than fertilization in this case. Drought conditions decreased steer gains per acre by 75% in unfertilized pastures, 42% in pastures fertilized with 50 units of N, and only 34% in pasture fertilized with 100 units of N.

Figure 1. Increased steer gain per acre per unit of added nitrogen (50 or 100 pounds of actual N/ acre) during normal rainfall years (2009 to 2011 and during the drought year of 2012.

Forage management for drought proofing your ranch depends on managing competition, grazing time, and rest. Stocking rates should be maintained at low to moderate grazing intensity, this leaves surface residue to increase water infiltration when it rains. Using managed rotational grazing can improve root health by providing rest for grazed plant, improving root health and speeding recovery from both grazing and drought. Weed control helps reduce competition for fertilizer and water resources from weeds and is beneficial for recovery by desired species. It is not something that can be done when things go south. These measures need to be in place and implemented before conditions deteriorate.